Friday, 18 February 2011

The Fool on the Hill

I've sold my house and am buying, in effect, a field. And a bit of wood and a share in a common, but basically a field. This is foolish. There is no planning permission on the field, and I'm unlikely to get any. Also, it's still possible that the deal to buy the field will fall through, but my house is sold. This is even more foolish. The field is five hundred feet above sea level, at the top of a very windy ridge. This is getting idiotic. Because I thought I would have more money than I've ended up with, I'm buying more land than I strictly need; and the consequence of that is that even if I get planning permission, I don't have much money left to build with. This is mad. Oh, and speaking of madness, I'm recovering from a bout of mental illness. At least, I think I'm recovering. So, this really is insane... Oh, and I don't have any income. At all. I could claim benefit - my doctor would certify I'm not fit to work (and he's more or less right) - but I've chosen not to. This is crazy.

But. But not that insane, I'd like to argue. Not wholly irrational. There are reasons. I'm not certain that they're good reasons, but...

I will have enough land to be self sufficient, which if I'd been more prudent I wouldn't have. The land, despite its altitude, is actually good; it's well drained, faces south west, and grew a barley crop last year. It's even soil-association certified as organic. I could live on what it can produce. I probably have enough wood to be sustainably self-sufficient in firewood.

Also, my breakdown over the last two years - which got quite bad - was at least partly because of the stresses of a failed relationship, and of working eighty-five miles from home. I couldn't sustain either of those things. I certainly couldn't sustain both together. I've no income because I lost my job, and I lost it because I could no longer do it. I'd planned to keep working until I could afford to buy my ex-partner out of my house, but I clearly can't do that. So I've sold my house in order to separate from my ex-partner. I couldn't have bought any house in my home valley on the money I thought I would realise from doing that, let alone for the money I actually did realise.

So the field is not necessarily a bad thing. Obviously, if I can't get planning permission I can't legally build a house on it. But there are workarounds. A couple of weeks ago - on two of the wildest nights of the winter - I slept in a yurt. It was a good, comfortable, pleasant, warm space. I could live in one (although I'd have to give away a lot of stuff). As it's a tent, it doesn't need planning permission. Of course, you're not supposed to live in a tent, but, on my own land and hidden by my own wood, who is actually going to stop me? And, importantly, I can actually afford a yurt - even a good one.

Of course that isn't the plan. The plan is to get planning permission to build something comfortable and interesting. But it is a fallback if that should prove impossible. And, in the meantime, I have to be living in my field in ten weeks from now - because I've borrowed a bothy for ten weeks, which keeps me warm through the rag-end of winter. But in ten weeks time it has other tennants, and I must be gone.

So this essay introduces a series of other essays which I'll post from time to time as the project develops, using as title my new persona:

The Fool on the Hill.

Wednesday, 2 February 2011

On Yurts

The last two nights I have mostly been sleeping in a yurt. No, scratch that. The last two nights I have entirely been sleeping in a yurt - it is much too cold to leave a foot stuck out for the sake of a meme.

Outside, that is. Inside the yurt it is quite startlingly warm - certainly much warmer than I would be at home. A small centrally located woodstove heats the space exceedingly effectively. My second night in the yurt was, coincidentally but rather fortunately, the windiest night for a year - and one of the wettest. In the depths of this cold, wet, violently windy night in early February, the yurt was cool. But not colder than I should have been at home, not draughty, and (apart from a slight anxiety about a tree actually falling on it) not insecure.

This yurt is from Yurts Direct, and is, I believe. authentically imported from Mongolia. It's about 6 metres in diameter - frankly spacious and generously propeortioned; it is in itself a work of art. The curtain which lines the wall has a damask weave with a crysanthemum pattern, in fabric somewhere between ivory and gold. The poles of the roof - some eighty-one of them - together with the roof crown and the two posts which support it, are of a burnt orange colour apparently individually hand painted, and yet with a regular repeating pattern, as are the doors. The doors comprise two inner doors and a single outer door, all housed in a substantial and rigid wooden frame, with windows in the inner doors and on either side of the door opening.

A curious thing is that while there is a cord to tie the outer door open, there appears to be no mechanism for latching them shut, short of leaning something heavy against them. And this matters, since it's been extremely windy both nights. Which raises another issue - there's remarkably little sound insulation. While only occasional gusts rattle the crown cover, the noise of the wind in nearby trees is loud.

At the eaves the roof is certainly less than 1500mm from the floor; at the crown ring, about 2300, and at the top of the crown perhaps 2500. What this means in practice is that I can't stand upright within one metre of the wall, but in practice this doesn't matter since the space against the wall is naturally used for seating and storage, leaving the main area of the floor free.

Although the only fenstration is the (small) glass panels in the door and the transparent sections of the crown cover, they let in a surprising amount of light in daylight - and from my bed at night I could see stars.

The floor of this yurt is made of (apparently) chipboard flooring panels, which are supported off the ground on sturdy wooden joists laid on pillars of concrete breeze blocks. The floor is not part of the package you get from Yurts Direct, but is something you have to construct for yourself.

This yurt cost £4,000, and similar yurts are available now for £4,495 (Yurts Direct describe it as a 'size 5'). Quality yurts made in Britain by (e.g.) Woodland Yurts cost about the same or slightly more. That isn't an unreasonable price - there's quite a lot of work, and a fair bit of material, in one of these.

As low cost housing for rural Scotland, how does it stack? This yurt is, I think, generous and elegant living space for one, and adequate but a bit tight for two. Indeed, a single person would get away with a smaller one. It doesn't, of course, have anything like a bathroom, which would horrify the planners. It is adequately warm with the burner lit, and clearly adequately wateerproof - this yurt, which has been up all winter, shows no signs of water staining anywhere, despite the relatively low pitch of the roof.

Most of the materials could be sourced locally in rural Scotland. The frame is wooden. The insulation is wool felt - and let's face it, we're not short of wool. The outer covering is canvas, which could be flax (in this case it isn't, but it could be). In terms of durability, the frame, with reasonable maintenance, is likely to be good indefinitely - certainly for a lifetime. Also, individual components of the frame can be individually replaced with little impact on the surrounding structure.

The canvas covering is likely to have to be periodically replaced, perhaps every ten years. The layers of felt will also need periodic replacement. Apparently it is a good thing to dismantle and overhaul a yurt at least annually, and I can clearly see the sense in this.

The major problem with a yurt in Scotland is of course damp. If the stove is not regularly lit, moulds and mildew attack the canvas and felt. This shouldn't be a problem in a yurt that's permanently inhabited, provided there is a reasonable supply of firewood. There's obviously a risk of fire; a yurt which I have seen which caught fire burned to little more than a ring of ashes. In a yurt made predominently of natural materials there should not be a great problem with toxic fumes, and, being all one space, there isn't a complicated route to find to the exit. So whether the risk to life of fire in a yurt is greater or less than the risk in a conventional structure I couldn't say. However, it's certain that in the event of a fire very little of what is in the yurt could be saved.

I don't know what happens to wool felt in the long term. People I've spoken to talk about infestations of mites or insects - probably something like the chitin-eating silverfish - and this sounds somewhat unpleasant. But inorganic felts - fibreglass, for example - also present problems, not least long term environmental problems in disposal.

The stove in the yurt I stayed in is a locally made one, not of very high quality, but it stayed in both nights even with my inept management. Good stoves suitable to use in a yurt are, obviously, available.

In summary, I was sleeping in the yurt to test-drive it - to get a feel for whether it would be a temporary dwelling I could survive in until I get planning permission for my permanent dwelling. And the answer, simply, is that it is. But - and it's a big but - it's not cheap. The combined cost of the yurt and the platform it sits on and a suitable stove add up to a fair proportion of my available building budget. On the other hand if you turn the equation on its head and say the yurt is the permanent structure - and it is comfortable enough that one could do that - then suddenly it does not look expensive at all, but on the contrary very cheap.

Sunday, 23 January 2011

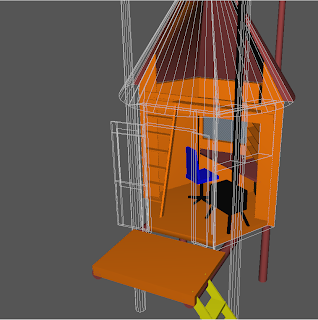

The Hide

The modular sousterran idea is all very well but I have to survive somewhere until I have planning permission to build it. I can't afford to rent, so I'm pretty much going to have to live – while I'm at home, at any rate – on my land. This design exercise is to see what is the cheapest and least conspicuous living space I think I can cope with through two winters. Cheap obviously means small, but surviving through winter means reasonably well insulated.

This design is fundamentally based on my present bed, which is an IKEA loft bed with a desk and bookshelves underneath – a quite cosy and comfortable working space. I started from there and thought, 'OK, how much more do I actually need'. A design constraint is the spacing of trees in my wood. They've mostly been planted at pretty exact two metre intervals, although the rows don't precisely align. I can, of course, cut trees down – it's my wood, and, furthermore, it needs to be thinned – but in the interests of hiding the hide I don't want to cut too many down. It won't be good for the planners to know I'm living on site while I'm applying for permission to do so.

The plan is a hexagon of side 1200mm – basically, that's the biggest hexagon I can fit onto two sheets of plywood. I could get a bit more space by using a 2400mm cuboid, but cuboids are ugly and that's 25% more wall. Also, it's easier to fit the hexagon into the wood than the cuboid, which would definitely need trees cut down.

It's beneficial to have the cabin off the ground to avoid damp. Having it head-height off the ground means you can use the area under it as sheltered storage. There should be no need to kill the trees that support it, two poles lashed crosswise to four living trees should be fine.

The downside of the hexagonal plan is the bed ends up an odd shape – it is 2400mm long on its long side, but only 1040mm wide and only 1200mm long on its short side. It's big enough, I think, provided any concubine is friendly!

The hide as designed has a wood stove for heating and basic cooking, but there is no lavatory, bathroom or laundry – those facilities will be available in the Void. A stove is quite expensive, of course, but I think it's essential.

Construction

My idea is to construct the hide as two modules and six roof panels off site, under cover, transport those modules to site without their insulation and final outer cladding, erect them, insulate and clad them. The module structure will be primarily WBP plywood with softwood framing, assembled using the wood epoxy saturation technique, so pretty durable. Insulation will probably be 100mm fibreglass felt, although if I can find something more ecological that I can afford I will. All panels, including the floor, will be insulated.The rear module will contain the built-in desk, bookshelves, cupboards and bed. The front module will be considerably simpler, containing the bunk ladder and wall cupboards. The modules will bolt together – the reason for applying cladding on site is that the cladding will cover the bolts. Also, of course, the unclad modules will be lighter and easier to manhandle.

The cladding will be tongue and groove softwood weatherboard painted with an olive drab exterior preservative paint, but nevertheless is not expected to have the same life expectancy as the core structure – it can be replaced if needed. In order to prevent nailing the cladding on from breaching the encapsulation of the epoxy-protected core structure, sacrificial 25x50mm strips will be bonded on for the cladding to be nailed to.

It would be much simpler and cheaper to make a lower, hexagonal roof. Making the roof conical is an architectural conceit. The roof will almost certainly have to be cut on site to make room for the trunks of the supporting trees. It is built as six panels each having a flat sheet of plywood as its inner surface, a flat plywood soffit board, and an outer surface planked with tapered softwood planks. Between the inner and outer surface will be insulation as on all other panels. Some arrangement for ventilation will be made at the eaves. One of the panels will have an aperture designed for the stove pipe to pass through. After the hide has been erected the roof will be covered with tarred felt, and the final top cone, probably of stainless steel sheet, will be fitted.

Living

The hide described in this paper really is small, and in cold wet weather is bound to be claustrophobic. Nevertheless with a small wood stove in a small and well insulated space it should be cosy, even in very bad weather, provided the door fits well! In better weather, and to entertain anyone, it needs to be extended, and this can most simply be done by providing an awning. An awning to provide a 5 metre square sheltered outdoor space would mean felling four trees.It's probably not possible to provide a cludgie in the wood as the drainage ditches all connect back to the Standingstone burn and are sufficiently closely spaced I doubt you could get the requisite distance from running water. I'll check this, because some sort of loo would be a good thing.

A stove of the sort used in yurts would provide adequate basic cooking; in practice except for baking bread I don't often use an oven. For more elaborate cooking we will probably eventually have a cooker in the Void.

I'm not sure about electricity – some form of light is going to be necessary in winter, otherwise it's going to be a little grim; and it would be nice to be able to use my little laptop without having to go up to the Void every day to recharge it. But solar panels are not going to work in the wood, and mains is not on for all sorts of reasons. Even a small wind generator would attract attention.

There's obviously nowhere near enough storage space in this for all the clothes I use regularly, or all my tools, computers, books and things. This is minimalistic, temporary living, and most of my gear will have to be stored in the Void.

Thursday, 20 January 2011

Sousterrain revisited: there is a plan B

Having considered my earlier note on the design of a sousterrain for a month, I'm now going to rip it up and start again.

Reasons for not building in concrete

Reasons for building in timber

Lightweight structure

Overburden

Temporary structures

Hybrid structure

Plan B

- Start immediately (in March) to build one experimental dome in epoxy encapsulated timber with an intention to have it habitable by May

- Erect that in a suitable place 'off site' (and not earth sheltered) until planning permission has been obtained.

- When planning permission has been obtained, dig out the platform (the entire platform large enough for all four planned domes).

- Lay suitable foundations for one dome.

- Disassemble the prototype dome and re-erect it on-site.

- Back-fill over that dome only, leaving the remainder of the platform clear.

- Occupy that one dome, at least for winter 2011-2012; build other domes in a similar fashion at funds allow.

Tuesday, 18 January 2011

The joys of data transfer

OK, so, at this stage the main thing this blog is for is to find out how to import existing blog posts into Blogger. Brief summary: my existing blog uses a blogging engine I wrote myself back in 2000; it's quite a good blogging engine but it's not used by very many people because I didn't promote it enough back in the day, and so it's time to end-of-life it and migrate the existing users to something else.

Blogger has a mechanism for exporting and importing blogs. So, I thought, it ought to be possible to generate the export format, which is documented here, from my existing data and then import that. From the documentation it was clear that the format was slightly bizarre - a well formed XML wrapper around data which is actually XML and presumably also well formed but is represented as text. However, I generated stuff that looked right to me according to the documentation, and it failed to import.

Worse, the error message given was terse to the point of unusability, and there's apparently no documentation of the error codes available on the web.

So the next thing to do was to export this blog from Blogger, and see whether the export file format looked anything like the documentation. And, guess what, it sort of doesn't. Which is to say that while the file format shown in the documentation is a very small subset of what's actually generated, it is such a noddy example that it doesn't even nearly represent what one needs to generate.

And, of course, there's no guarantee that even if I did succeeded in generating all the cruft that's in the format as generated by Blogger, I'd get my data to reimport - since the format includes magic identifiers which may represent objects in Google's persistent data space.

So it may be time to think of other ways to work around this.

Monday, 17 January 2011

End of eating dogfood

I can't help being slightly sad.

Monday, 29 November 2010

Site specific low cost housing for a windy site

Part of the issue of building housing on the site we're considering is the wind speed, which is high. I imagine we're all going to want homes which don't take a lot of energy to heat, and the wind-chill effect on exposed walls is going to be considerable. The parts of the site which are most exposed to the wind are also the sunniest – the southern and western slopes. Of course, one can insulate, and straw bales are worth considering.

Sustainable?

Visual impact

Elements

Dome segment

Pillar

Flying Buttress

Eve

Building method

Dig back into the hillside

Lay drains

Level platform

Pour slab

Erect pillars

Erect uphill walls

Erect terrace retaining wall

Part-backfill the uphill side

Erect flying buttresses, eves and (possibly) lintel arches

- Embed a tensile steel reinforcing belt as low as possible in each dome;

- Construct separate armatures for each dome and leave them in place until all domes are cast and cured.

Erect domes

Fit chimney outer

Fill valleys between the domes

Lay upper membrane

Backfill

Install glazing

Fit out interior

Rough costings

| Sousterran: quantities and mass | ||||||||||||

| Concrete option | Cladding | |||||||||||

| Constants | Unit | Item | Unit | Price | per sq m | |||||||

| Mass of 1 cubic metre of concrete | 2400 | Kg | Bituthene 3000 | 20 metre roll | £163 | £9.03 | ||||||

| Mass of 1 cubic metre of soil | 1700 | Kg | Styrodur 3035CS, 30mm | 14 sheets at 1250x600mm | £70 | £6.67 | ||||||

| Price of 1 cubic metre of concrete | 100 | Pounds sterling | Styrodur 3035CS, 60mm | 7 sheets at 1250x600mm | £70 | £13.33 | ||||||

| Price of 1 8x4 sheet 15mm exterior ply | 40 | Pounds sterling | Total, with 30mm | £15.69 | ||||||||

| Price of 1 sq metre concrete blockwork | 10 | Pounds sterling | Total, with 60mm | £22.36 | ||||||||

| Dome radius (long axis) | 2.4 | metres | ||||||||||

| Area of dome floor | 14.98 | square metres | ||||||||||

| Area of dome surface | 36.19 | square metres | ||||||||||

| Number of wall panels | 11 | at | 4.8 | sq metres | ||||||||

| Elements | Area sq m | Thickness m | Volume cu m | Mass tons | Concrete Cost | Cladding cost | Number of | Total cost | Total mass | Shuttering sheets | Shuttering cost | |

| Floor | 104.83 | 0.1 | 10.48 | 25.16 | £1,048 | £399 | 1 | £1,448 | 25.16 | 1 | £40 | |

| Dome | 36.19 | 0.1 | 3.62 | 8.69 | £362 | £809 | 4 | £4,685 | 34.74 | 42 | £1,680 | |

| Dome segment | 6.03 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.45 | £60 | 24 | 34.74 | 7 | ||||

| Pillar | 0.5 | 1.2 | £50 | 17 | £850 | 20.4 | 6 | £240 | ||||

| Eve | 1 | 2.4 | £100 | 5 | £500 | 12 | 4 | £160 | ||||

| Flying buttress | 2 | 4.8 | £200 | 4 | £800 | 19.2 | 6 | £240 | ||||

| Wall | 4.8 | 0.1 | 0.48 | 1.15 | £48 | £75 | 11 | £1,357 | 12.67 | 0 | ||

| Overburden | 104.83 | 0.2 | 20.97 | 35.64 | £0 | 1 | £0 | 35.64 | 0 | £0 | ||

| Subtotals | 50 | £9,639 | 194.56 | £2,360 | ||||||||

| Total, cost | £11,999 |

Thursday, 18 November 2010

Practicalities of 'affordable' housing

This document attempts to address how in practice we would implement an affordable housing policy if we choose to do so.

Rural housing burden

To what should the burden apply?

- The burden could apply to the dwelling and curtilage only

- The burden could apply to the holding

Can we use other burdens?

Alternative price cap models

Land

The existing farmhouse

Match price

'Affordable' price

'Just' price

'Reasonable cost' price

Hybrid schemes

The 42 day rule

Wednesday, 17 November 2010

A Just Price for housing

Standing Stone: reasons for adopting a 'just price' for housing

Applying this to Standing Stone

The just price

Land:

|

£2,500

|

Fees and contractors

|

£7,500

|

Sweat equity

|

£10,000

|

Structure

|

£40,000

|

Total

|

£60,000

|

The affordable price

The just price revisited

Non-idealistic argument for a just price formula

Wednesday, 31 March 2010

Auf Essen in Deutschland

I've spent the week in Germany, where I've been performing a safety audit on a device made by a German subsidiary of a Swiss company on behalf of an English subsidiary of a French company. I write this sitting in France, fifty metres from Switzerland, while waiting for a plane to fly me to the Netherlands and thence home to Scotland. It's all remarkably painless.

But let's talk about Germany. Lots of the things you thought you knew (or I thought I knew) about Germany turn out to be true - or at least, turn out to be true of small towns on the fringes of the Schwartzwald. My view might be slightly influenced by the company I was auditing, by the fact that that Swiss-owned engineering company was absolutely obsessive about quality in everything they did (including hospitality). It was engineering of the kind I associate with Germany: always up to a quality, never down to a price. Over-engineered rather than under-engineered; good and thoughtful design, but emphasising sturdiness and durability over style.

The taxis were spotlessly clean, their drivers unfailingly courteous. The factory was clean and efficient and all the staff positive, relaxed, confident and happy to explain their work. The hotel was extremely well fitted and comfortable (and clean), the rooms generous and luxurious, the staff helpful, friendly and welcoming. They were mostly middle aged, not young; I think almost entirely local; and the ratio of staff to guests higher than you'd find in anything but the most upmarket British hotel. Yet the cost of a room was exactly the same as in a grubby corporate flea-pit in East Kilbride - where you would not have got the delicious and varied breakfast.

Which brings me to food. The company we were auditing treated us as guests; not only did they provide us with restaurant-quality lunch each day in their staff canteen, they took us out to dine every night, at a total of three different restaurants; twice the one belonging to our hotel, once a modern restaurant in the local administrative centre, and once... I'll come to that.

So what is German food like? Sausages and sourkraut? Chips and cream-cakes? Errr... no. We did eat a little sourkraut - several varieties of it, all good. We ate noodles, of kinds I'd never heard of before, let alone seen - nothing like Italian noodles. We ate dumplings. We once ate chips - once. We ate a simply extraordinary quantity of meat. We ate home made icecream. I didn't eat sausage at all (although a number of varieties were available at breakfast). Slightly to my disappointment I didn't eat a proper Schwartzwald Kirsche Torte - I could have, but I simply didn't have room (my abstemiousness at breakfast was for the same reason). I have eaten more this week than I eat in an average fortnight.

So, what is the food like? In one word, delicious. Extraordinarily good. Exceptional. Second, in my experience, only to Malaysia. Everything was of superb quality, freshly prepared, not over fancy. The effete over-complicated confections of British television cooking were nowhere to be seen; nor was fast food, or junk food. In the urban centres we did see a few Indian, Chinese and Vietnamese restaurants, and we did see sausageinnabun shops. But the places we went to served food which was proudly local, unashamedly German, unquestionably fresh-cooked and utterly excellent.

Until the very last night - last night - which was completely different. We drove up into the forest, up steeply climbing twisting roads which would be a joy to cycle in summer, to an ancient farm-house turned gasthof. The whole place was wooden, over four hundred years old. We went into a simple, homely dining room which would hold twenty people at the most, but which was empty but for a man sitting alone and the four of us. A pretty young waitress who spoke no English brought us simple paper menus, and came back after a few minutes to take our order. I chose a venison ragout with noodles, which sounded good.

So much, so normal. And then it all changed.

Mien host came in, a tall and powerful old man called Saxo, wearing casual countryman's clothes. He spoke a little English but was much more comfortable in German. He sat down with us for a few minutes, talking, and then said he'd shot a wild pig, and would we like some? After not a lot of discussion, we agreed we would. Was it spit-roasted, someone asked? No, it had been baked in the oven, after the bread he'd be serving with it. Saxo also said he had some mead, would we like to taste?

He disappeared into the back, and shortly reappeared bearing an enormous ox horn in a wrought iron stand. I joked that it must be an aurochs horn, but in truth I don't know where he got one so big; it wasn't old, and was by far bigger the horn of any domestic breed I know of except perhaps a Texas long-horn. He offered this to us and I realised it was full of mead. How much mead fills a horn like that? I haven't a clue, but it must have been at least two litres. I was certain that between four of us - and one a driver - we'd never empty it. So we chatted round the table with Saxo, and drank his (wonderful) mead, passing this epic horn from hand to hand, until the chef appeared.

The chef was a man as big as Saxo, and with the sort of belly on him a good chef should have. He greeted us, spoke to Saxo, and they both disappeared into the back. After a few moments they reappeared, bearing a trencher. A trencher? it was at least four feet by two, of sturdy oak. It filled the table, clearly leaving no room for such effete nonsense as individual plates. On it. besides two baked quarters of a substantial pig and a large loaf of rough bread cut into thick slices, were two large crocks of gravy, baked apples, baked potatoes, sweet corn, and a mountain of roughly chopped mushrooms (which, it transpired, were the only ingredient which had been bought in). Oh - and four very sharp knives. No forks.

Four people - four people could not possibly eat all this.

Four people very nearly did. There were some potatoes left at the end, and an apple, and perhaps a kilo of pork on the shoulder. We gorged ourselves. We all gorged ourselves, despite having already overeaten for three days, because it was so extraordinarily delicious, so utterly delectable.

And when, finally, we thought we had eaten all we possibly could and the trencher had been removed, the pretty waitress (who, it transpired, was not German but from Drakula's home village in Transylvania) persuaded us all to have some home-made ice-cream with advocaat; and Saxo reappeared and persuaded us to have a schnapps. The waitress and the other guest (an engineer from Bratislava in Slovakia) joined us, and together we conversed in a happy mixture of German, English, French, a bit of Italian, a bit of Dutch, and some Slovak, while the mead horn continued to circulate.

We could have had that meal - in that place, in that environment - any time in the past four hundred years; there was an electric light but it was no brighter or more intrusive than a candle lamp. Apart from the potatoes and sweet corn, we could have had it any time in the past millenium.

At the end of it all we went back to the hotel very late. I was drunker than I've been in twenty years - and probably happier. The mead horn? It was empty.

The fool on the hill by Simon Brooke is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License