Saturday, 26 March 2011

Shapes in the landscape, and aerodynamics

I've now discussed the singlespace design with a lot of people, and got useful feedback.

Several people have queried having the loo in the singlespace. Actually, that was never the plan. The plan is to have a cludgie about 50 metres away in the wood. However, this is a house to grow old in, and while it's one thing to go fifty metres into the wood on a warm summers day at fifty five, it may be a different thing on a cold winters night in twenty years time. So the design has to have an account of where an indoor water closet will go. And just at present it doesn't.

Another friend asked where I would put my bikes. Again, a very good question which this design really doesn't address. And it does need to. There's no point in having a dwelling which is almost invisible in the landscape if it's surrounded with ugly sheds.

Which brings us to my objection: the isolated geometric cone, even if covered with turf, isn't a natural shape. Granted, as an architect friend has pointed out, there's nowhere you can see the cone against the sky - it will never be skylined, because of the rising ground behind it. But it still isn't a natural shape.

Also, significantly, rain which falls on the north half of the roof drains north. Of course there needs to be thoughtful drainage around the north half of the building, but still adding more water to the problem isn't helpful. From that point of view, building a gable from the apex of the roof north-east into the hillside would both make a (somewhat) more natural land shape and reduce the drainage problem.

However, you end up with an unlovely bastard structure, and this in a building in which the structure is necessarily exposed. I'm still somewhat in love with my twisted cone roof. And my architect friend feels that the flat planes of the gable roof will look as unnatural or more unnatural in the landscape than the cone.

So there are a series of unresolved problems with the design.

However, the worst of the problems is one which should have been obvious to me. That conical roof is going to generate a huge amount or aerodynamic lift, and mine is an exceptionally windy site. My architect friend, who pointed this out, said also that as I've designed it it is also floppy and will move in the wind. This isn't a crisis. He pointed out that I could brace the roof with tensile members, like a bicycle wheel. This resolves the floppyness - instead of moving like a jellyfish, it will move as a single rigid thing.

But.

But, it will still lift. That lift has to be contained. Which means the pillars have to act as tensile members, and must transmit lift to the floor. Which means that footing pieces for the pillars have to be cast into the concrete slab foundation, in exactly the right places. So I have to get the exact positions right before I pour the slab, and I can't shift things even by a single centimetre once it's poured.

All these things are design problems. All of them have to be resolved. But none of them makes this design unusable. I shall continue to think.

Monday, 21 March 2011

Singlespace joinery detail

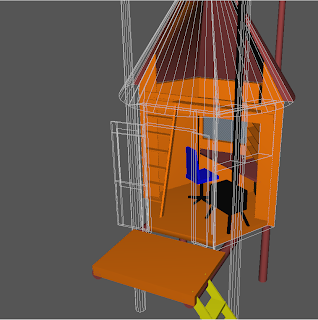

In my initial sketch of the structure I discovered that in order to avoid complex joins at the pillar heads, each pillar/ring beam assembly has to be rotated about the axis of the building by an odd multiple of the rafter spacing angle of the 'upstream' assembly. The rafter spacing of the inner ring is 15 degrees, and in both this drawing and its predecessor the second ring is offset by 15 degrees. The rafter spacing of the outer ring is 7.5 degrees; however, if you offset the outer ring by just 7.5 degrees it just looks odd and so in this drawing I've offset by 22.5 degrees.

Every pillar has exactly one rafter running through it, and the pillar is slotted to take the rafter. A single treenail positively locates the rafter to the pillar. Every pillar stands at the junction between two ring beam components. The ring beam components are joined with a mortice and tenon, and are then checked back into the pillar. Finally, they are lashed together round the back of the pillar, enabling a strong characterful joint. The ring beam components are notched slightly on upper and lower edges to positively locate the lashing. Each of the braces is checked into the pillar and fastened to it with two treenails. The brace is checked to accommodate the ring beam component it supports and fastened with two treenails; the joint might be a little more sophisticated than the one shown in this drawing, but I don't think it needs be.

The remaining rafters are laid on the ring beams and are checked in sufficiently to achieve a smooth,

fair, even cone to the roof. Because the rafters cross the ring beams at a range of angles each needs to be checked in individually on site - I don't think it would be wise to do this in the workshop and hope to get it right! the rafters obviously cross two ring beams, one at the upper end and one at the lower. At the upper end, the rafter is checked (although the sing beam might also be checked slightly); at the lower end, only the ring beam is checked.

Both ends of all the rafters are tapered upwards. The ends of the ring beam components are extended to a degree which is more than that strictly required for joint stability and again tapered. Exposed edges of rafters and ring beam components might be moulded with a router is there's time.

My intention at this stage is still to use plain ordinary manufactured patio door units for the front wall. Obviously these aren't designed to be fitted into this sort of structure, but they will save a great deal of complicated joinery and will just work, so I think it's worth using them and doing the necessary joinery to make them fit (and look reasonably good). I plan to put them immediately between the front pillars, inside the braces of the ring beam components, rather than either outside the pillars or inside the pillars. Obviously, between the tops of the patio door units and the roof there will be a series of complicated-shaped holes which will need to be made good with 60mm closed cell foam board faced with T&G boarding inside and out.

Finally - while this isn't strictly a joinery detail - both yesterday's drawing and todays show a polygonal wall for the back and sides of the structure. This isn't simply unnecessary - it will actually make fitting the waterproof membrane harder, because of the corners. So I now think a smooth circular wall with no corners would be preferable, and not greatly harder to build.

Sunday, 20 March 2011

Singlespace

I'm revisiting the design of my proposed home yet again. Yes, I know this gets boring. But it's probably the biggest decision I'll make in the next ten years - I need to get it right.

I do like the four dome design - the design I've called 'sousterrain' - I've been working on over the past six months. It's scupltural and elegant. I think it would have elegant internal spaces. Because it's modular, you can add on modules; you can build only part of what you intend in the first phase, and live in that while you build more. Which I would need to do, since I can't afford to build it all in one phase, either in money or (probably) in time.

It's also very challenging for the policy driven, risk averse, conventional planning authorities; but frankly anything I design or want to live in will be, so that's almost a non-issue.

Food miles

However, there are a number of arguments against the sousterrain design. The first is 'food miles'.

I came up with two possible constructions, one of which was engineered plywood, the other of which was concrete elements cast in engineered plywood moulds. Plywood is a wonderful engineering material from which you can make elegant, strong, light structures. But it is mostly made from rainforest timber and one really has no assurance that the forest is sustainably managed. And it's been shipped half way round the world. It's also quite an expensive material - the four dome design in plywood came out at £20,000 for the shell structure alone, which probably makes it unaffordable to me. It's because it's an exotic, highly processed material that it's expensive.

Building the four dome design in concrete is much cheaper, despite the fact that a great deal of plywood would still be required for the moulds. Concrete is an amazingly cheap material, in financial terms. But it isn't cheap in energy terms. Making the cement for concrete embodies a huge amount of energy, with a very real carbon cost. And, in any case, it isn't made locally - from the point of view of Galloway it is again an exotic material, one which is shipped in.

I've been reading a lot of books about dwellings written by hippies lately. Mystics. People who feel that there is inherent merit in building in the stuff of the landscape in which they build - in wood and stone from the site itself. It's a romantic idea. But, beyond that, it's how most houses were built prior to our parents' generation; and, in all likelihood, how most houses will be built after our childrens'. In actuality, I could build with the materials of my own croft - obviously I could, people have been building dwellings in Galloway for four thousand years. But I am, although a hippie, a pragmatist, I hope, not a mystic. I could take the timber to build from my own wood. There is (easily) enough timber there - even for an all-timber structure.

Next, I could build the masonry parts of my building from field stone, as the people of Galloway have since the bronze age. On Standingstone farm, Auchencairn, I'm not short of stone. Now that really is practical - the embodied energy is significantly lower than building in concrete, and the stone costs me nothing except labour. I really could do it. Of course, I would still have to use cement or lime mortar, so the masonry isn't 'free' either in financial or energy terms, but it could be done and it would be better.

Pragmatics

The problem with using my own timber is that would take a year to season, and that means either I would be living in something temporary for the winter, or else burning my building money renting winter accommodation. And it would take milling, which would mean that either I would need to buy a mill (not cheap) or hire one of my friends who have mills to mill it for me. In practice I can buy timber of similar species and quality to my own timber for little more than the cost of using my own, and, provided I get planning permission, can build this year. But note - this is timber, not plywood. Plywood I don't have the ability to make.

The problem with using my own stone... The problem with using my own stone is that an underground or earth-sheltered dwelling in Galloway has to be very waterproof. Very. Of course, waterproof membranes are not native to Galloway, which is why Galloway people have historically not built earth sheltered dwellings. Traditional houses in Galloway did have high quality insulation in the form of thatch; and it's possible to insulate houses with wool, which also is produced in Galloway. But I do plan to use waterproof membranes, and the waterproof membranes I know how to use are designed to be stuck on smooth, flat surfaces. So I'm inclined just to use conventional concrete blockwork for my walls. Yes, it's embodied energy and it's an exotic material. But it's a heck of a lot quicker and easier and I end up with a reasonably smooth flat surface to which I can stick membranes which I know how to use. Outside that surface I'll use sheets of extruded (closed cell) polystyrene foam - another exotic material embodying energy - both as insulation and to protect the membrane from the soil. I'd already decided both those points when working on the four dome 'sousterrain' design. I don't need to revisit them.

After all, in the front of my dwelling I plan to use glass. It, too, is an exotic material, embodying a lot of energy, but I don't see many people too purist to use it!

The Single Space

OK, so, plywood I can't afford. Using a lot of concrete niggles at my eco-wannabe soul. And the costs of my designs - while not high, by the standards of modern housing - are hard to square with my budget. I need to rethink.

The shape which encloses the most area for the least edge - wall - is a circle. A circle is also the easiest shape to heat. And that takes me to yurts, about which I've been thinking a lot lately. Yurts are very simple and elegant structures. I've already decided that if I absolutely cannot get planning permission, a yurt is the way to go. Having slept in a yurt, I'm confident I could be comfortable in one. But it would be cramped. Even a large yurt of six metres diameter is only thirty square metres. Going up beyond about six metres you have a problem with the span of the rafters.

One American architect in one of the hippie books or websites I've read recently (I'm afraid I don't recall which one) solves this problem by arranging concentric yurt structures, with, essentially, intermediate tension rings supported by pillars. This is actually very similar to the design of round houses used by some native peoples of the south-eastern United States, and similar also to what has been inferred from post-hole evidence as the structure of a typical iron age dwelling in Britain.

A single circular space with the floor area of my four-dome structure - sixty square metres - would be slightly less than ten metres in diameter, or slightly less than five metres in radius. Which means two 2.5 metre rafters would span it with one intermediate tension ring.

A Subtle Twist

When I started thinking about this structure, I thought, as a western educated person, that naturally you'd run the two rafter sections coaxially, one in line with the other. But actually if you do that you get an incredibly complicated joint at the top of each pillar - a joint which it would be hard to make and harder to make strong. But if you offset the rings slightly, so that while each rafter is still radial to the structure it is no longer coaxial with the rafter up-roof from it, the whole structure becomes a lot easier to make, and also gains a subtle twist to the geometry which is elegant in a very unwestern way.

Internal Layout

I'm still - or, indeed, still more - resistant to the idea of internal partitions. I see this design as essentially a single space; I think its geometry demands that. But it's obvious that the stove needs to be at the centre, to provide even warmth. And it makes sense to put a (large) hot water tank also in the centre - since the hot water tank also forms part of the thermal mass which keeps the dwelling warm. A traditional yurt has two pillars supporting the ring into which the inner ends of the rafters fit; I've designed a triangle of three pillars. This triangle defines the 'warm core'; it contains the stove (facing south, towards the sun, and therefore the day side of the dwelling) and the water tank (behind it, to the north, in the night side). North of the warm core is the most shaded and most private space, so it makes sense to put the bed there.

It will be most welcoming if the floor between the entrance - the south, glass, wall - and the stove is largely clear. Kitchen preparation area is obviously needed near the stove, and should form one edge of this clear space. A dining area should also be near the stove and forms the other. Further back, the bath area needs a certain degree of privacy - not a great deal, since there are no near neighbours, but some. It makes sense to put this to the west, as there is some shelter from people approaching from the east. A work area needs protection from direct sunlight, which is hard on the eyes - but, at the same time, it's nice if there's a view. So it needs to be further back in the dwelling, and it makes sense to put it on the east.

What Doesn't Change

This is still a design to be built into the hollow I had already identified as the sousterrain site. It's still a design which will be earth sheltered - have earth covering the entire height of the north, east, and west sites; whose roof will be covered with turf; which will have 'patio door' sliding windows in its south wall, rather than a door as such. It's still a design which is intended to be inconspicuous in the landscape - although the low cone of the roof will be more obviously unnatural than the shapes you'd get from the four domes.

The Bottom Line

I started drawing this structure really as an experiment in exploring alternatives. What's startling, though, is how inexpensive it is. The materials cost of the shell works out at £6,020 - as against £11,999 for the four dome design in concrete, or £20,180.68 for the four dome design in plywood. Furthermore, while making the domes or the moulds for the four-dome design would need extremely careful finely detailed joinery, the 'singlespace' design is all simple carpentry. Unskilled people could actually help in building this. And, because it's simple, it could be built quickly - getting the shell completed in one summer season does not seem unreasonable. I'm now thinking of this design as my probable structure. Of course the verdammt planners won't like it any more than they would like the four dome design, so planning permission is still a major headache - but I don't think it's a worse headache, just something that has to be tackled.

Thursday, 10 March 2011

The Plan

Julie asks, what's the plan?

The plan, above all else, is to continue to live in the hinterland of Auchencairn, without having the money it now takes to buy somewhere here. That applies to all of us. The first stage of the plan has been to group together and buy a farm. That's completed; we've done it. Ruth has been the animateur of this stage of the plan, and as her share of the deal, she's got the farmhouse. So she doesn't need to build anything.

For the rest of us, we do. We don't, at this stage, have planning permission with which to do it. We're a mixed group, but usefully mixed. Boy Alex is a tree surgeon and feller, and intends to establish a saw mill. He's (naturally) thinking about a timber framed house, with Alice, who is a multi-media artist mainly working with film. James is an electrical engineer with a special interest in wind generation; if I'm up to date with his plans he's planning something like an earthship for himself and Vicky, and their young family. Justine and Si run a business providing up-market accommodation - mostly in yurts which they make themselves - at music festivals; their plans are slightly longer term but they have been talking about a straw bale or cob house to live in; they will use their land as a campsite and perhaps run yoga courses. Finn is a blacksmith, and doesn't actually plan to live up at the farm; but he is planning to move his workshop. Godfrey is a shoemaker; his plan is for a craft workshop and gallery, and perhaps a cafe, in the existing byre building. He also plans to establish a market garden, although in the end it might be someone else who does that.

And then there's me. I don't really have any special skills, but I'm good at learning stuff and good at making things happen. I'm planning to build an earth-sheltered structure, mostly because I want to. The details, and the thinking about it, are in other essays on my blog. For the rest, I've bought seven acres of pasture and three of spruce plantation; I'm planning to plant some of my pasture with mixed native tree species to provide shelter (it's an extremely exposed, windy site). If I can get enough other people to share in the work I might keep a couple of milch cows on my pasture to provide milk for the farm; otherwise I'll probably buy a few weaner stirks each spring, and slaughter them in the autumn for beef. I'll also have a vegetable garden, although how good I'll be at making that work we'll see.

I'll need to generate my own electricity, because my croft is too far from the powerline for me to be able to afford to use mains; but fortunately there is no shortage of wind. We do fortunately have mains water, but if we didn't there are springs we could make use of - this is Galloway, after all!

My existing plantation should provide sufficient fuelwood indefinitely for my home, and I will progressively replant it with native species as I extract. But in addition, I share with everyone else in the 'commons', the land which we haven't allocated to anyone individually, and that includes 15 acres of woodland - mostly spruce - which will provide some construction timber and probably provides sufficient fuelwood indefinitely for everyone.

No-one's plan is to live exclusively off their land. We none of us have enough land for that. And we won't be operating the farm as a strictly commercial farm, more as a collection of crofts.

The extent to which we'll work as a community is still very much fluid, and will develop organically. In the short run, we're all broke and will have to help one another out with things. In the longer run, I'm sure things will develop. We're all nervous about the amount of organisation, meetings and time that goes into running existing communes like Laurieston Hall, but inevitably there will be many things which it will just be sensible to do communally. For example, we're currently discussing whether we should buy a communal digger.

All of which is to say, there isn't really a plan, beyond some broad brush strokes. We have a farm - in a startlingly beautiful (if windy) location. We have a bunch of interesting, capable people. We are going to live there (although that may take some robust negotiation with the planners). Stuff will happen.

It's an adventure, and the second phase - settling in - starts now.

Tuesday, 8 March 2011

Clutching at straws

In my last essay I discussed the possibility of using wool as insulation. After all, as I said, we have wool. The problem with using wool as insulation in the walls is that it has no structural strength and is not weatherproof; it must be packed into structural, weatherproof boxes. The wool is virtually free, but the boxes come expensive.

Well, OK, we do have wool. But we also have straw (and a square baler to bale it). This year we're growing three acres of barley on my croft, and thirteen acres across the farm as a whole; and no-one else is going to be bidding for the straw, except as horse bedding. Straw bales provide both structure and insulation. Indeed, the first straw bale houses, on the north american prairie, also had turf roofs, so there's no doubt whatever that they can sustain the compressive load. The insulation values - tested, again, over a century of prairie winters - are very good.

In straw bale construction, you need, of course the bales. In order to tie them strongly together, you need a certain amount of steel rod - about two or three metres for each square metre of wall. And you need a rodent-proof render on both inside and out. On top and bottom you also need something rodent-proof; boards are possible, but so is render. All this is cheap - as cheap as or cheaper than concrete blocks.

The bales must of course be used after the harvest - so September - and must be laid and rendered dry. Dry weather is not guaranteeable in Galloway autumns, so there would be benefit in having the roof up first. Furthermore if the roof isn't up first, there isn't a lot of time to get it up before winter closes in. Of course, if the roof is to be up first it must be supported on pillars. Of course, those pillars could be temporary - my proposed roof structure is after all, as Pete objected, floppy, and so will accommodate a slight movement as the pillars are removed (provided that it is slight!).

All this begins to look very like a plan. It is cheap - actually the cheapest structure I've so far costed. It's also extremely 'green' - low energy, low carbon cost. I continue to assert that the zero carbon house is impossible to achieve - this one will have some sort of plastic membrane on the roof, and will have glass windows; furthermore a certain amount of cement and quicklime will be needed for foundations and render. But this is probably as close as it is possible to get. And it makes use of materials - timber, straw, wool - which we produce on site. I think I have a plan.

Home

My parents rented the top cottage on Nether Hazelfield in 1965, when I was ten, and from that time I've always seen Auchencairn as home. Although my parents bought a house in Kirkcudbright in 1969, I returned to Auchencairn in 1977 to set up a pottery in the old mill. That business lasted until 1981, when Mrs Thatcher had her first recession and eight of the thirteen potteries in Dumfries and Galloway ceased trading, including mine. In 1982 I went away to University, and after graduating, worked as an academic in Artificial Intelligence for three years before becoming chairman of a spin-out company, attempting to market the products of our research. That company traded successfully until the recession of 1991, when it was wound up, and I returned to Auchencairn.

I've been here ever since. This is my home.

If I'm to stay here now, however, I need a home I can afford; and house prices in the village itself have become very silly, as more and more houses have become second homes or retirement homes for people who have not had to earn their living in Galloway's labour market. Consequently the Standingstone proposal has seemed to me a risk worth taking - it seems to be my best chance of staying in the valley. I appreciate that it is a risk.

If I'm to have a house here, it has to be small, cheap and simple. It has to be simple because I cannot afford to pay someone else to build it. It has to be cheap not only to build, but also to run, because the years in which I can continue to earn my living are limited. And, because it's a house to grow old in, it has to be durable enough not to need much maintenance in the next thirty years. All these things do not mean, however, that it shouldn't be well designed. On the contrary, each of them means that it should be well, and thoughtfully, designed. Building a house is something I'm almost certainly only ever going to do once; I want to get it right.

What I want is a house which vanishes into the landscape - one which, when natural planting has grown up around it for three or four years, a stranger can pass within fifty metres of and not know it's there. I want a house which is naturally warm, which doesn't take a lot of energy to heat. I want a house which is graceful and sculptural. I believe that this can all be done. More than that, I believe I can do it. I acknowledge that what I want isn't 'traditional' or 'vernacular' in Galloway, but it is nevertheless a designed repsonse to Galloway's particular geography and climate - and to my budget and needs.

Sunday, 27 February 2011

Review: Oehler, M: The Underground House Book

Mike Oehler is an autodidact, and a man - he admits it, nay, proclaims it - of strong and idiosyncratic opinions. He has a recipe for building small dwellings cheaply in Pacific Northwest USA - which is to say it's as wet as western Scotland, warmer in summer and considerably colder in winter. He designs houses that I could afford to build using materials which are - with the exception of the polyethylene membranes which are key to his system - considerably more ecologically sound than most modern building materials. He makes substantial use of roundwood poles - which I have in abundance for the cost of cutting and seasoning them.

All these are reasons I should take him seriously. And yet, I'm wary. He's built - or claims to have built - remarkably few dwellings (two, as far as I can see, although people using his method have built many more). He doesn't seem to use any moisture barriers in his floors - in fact, he extols the virtues of earth floors. I simply don't see that working in Scottish conditions (In fact in the 'Update' section at the end of the book, Oehler now has a membrane under the floor of his house - which is now carpeted).

The other thing is that I strongly suspect that if you showed one of his houses to any self respecting British Building Control Officer you'd get something between a hearty guffaw and a shriek of horror. Indeed, Oehler's own response to building standards is clearly expressed on page 100 of his book: 'will a home built with the PSP system pass the code? The answer is, sadly, no... you may move to an area which has no codes...'

Well, you may. But I want to build my home on my land in my home valley, so I can't. I could adopt Oehler's alternative suggestion, of evasion... but the less said about that the better.

Finally, a note of caution about the title. Oehler's quoted prices relate to the 1970s; and even then I think a certain amount of creative (or merely forgetful) accounting was involved.

Nevertheless Oehler's book is both thoughtful and thought provoking. I'm glad I read it, and will continue to mull over it.

Sunday, 20 February 2011

To cast or not to cast

To cast concrete or not to cast concrete, that is the question. 'Tis undoubtedly nobler not to. Cast concrete requires a huge amount of energy, and so inevitably has a high carbon cost. On the other hand, provided it's done right, it will stand and be useful for hundreds of years, so that energy cost is ammortised - potentially - over a very long time. But here's the rub. I don't need a dwelling that will stand for a very long time. I need a dwelling which will be reliably warm and weathertight for thirty years. After that, it's someone else's problem, and someone else may not choose to live underground.

The wood/epoxy alternative is probably but not certainly good for thirty years. If it starts to fail in twenty years, when I'm in my mid seventies and probably pretty broke, that's going to be bad news. I don't think it would, but it might. Also, the cast concrete structure is remarkably cheaper, and remarkably easier to insulate, than the wooden one. Given how tight I am for money, that's a very significant consideration.

Casting on-site is definitely out. I can't get a readimix truck to site, and I can't quality-control the concrete I can mix for myself on site. Also, the shuttering cost of casting on site is high because it would be necessary to cast a whole dome in one go. I had ruled out my original idea of casting off-site because I had thought that I could not afford the heavy equipment to move stuff on site. But Boy Alex's Unimog can do exactly that. Casting off-site is once again an option.

If anyone thinks that, like Hamlet, I'm labouring this decision, well, I am. This is almost certainly the biggest decision of the rest of my life.

Saturday, 19 February 2011

Structure Review

OK, I'm getting very close to the point where I have to commit to a structure for my new home. I have to apply for planning consent, and I have to do it soon. If - improbably - I get consent quickly, then I can build this summer. And that would solve a lot of problems.

Of course, I can't actually afford, now, to build the full structure I want for the long term, so it has to be modular: I have to be able to build some 'now' and some 'later'. So let's again review the arguments and the options.

Conception

The original conception was for an underground structure sunk into a south-facing slope, comprising four hexagonal domes each 4.8 meters in diameter: one for services, one for kitchen, one for day, one for night - where the 'service' dome held bathroom, store and spare bedroom. The roofs were domed mainly because, in concrete, that's a good self supporting shape, and form followed function. They were 4.8 metres in diameter mainly because they would be cast over fundamentally plywood forms, and plywood comes in 2.4 metre sheets.

Underground is important both for insulation, for landscape considerations, and, most importantly on the very windy site, gets down out of the wind. The alternative of, for example, a timber framed straw-bale building would be both very intrusive in the landscape and very exposed to wind.

The south slope is important because it allows a fundamentally underground dwelling to have passive solar gain through south facing windows. In any case I've deliberately bought a south-facing slope for exactly this reason. An underground dwelling on a fundamentally flattish site in Galloway would have more significant problems with drainage and with daylight. I could get a more conventional house out of the wind by sheltering it behind my wood, but then it would lose the south aspect and consequently the passive solar gain.

The case for a hexagonal grid is a bit less compelling. Mass produced furniture is designed for rectangular spaces. Deliberately choosing a non-rectangular space means that much more of the interior furniture must be custom designed, which pushes the cost, either in money or time, up. However the human eye is very good at finding linear features in a landscape. Straight lines are very obvious, very noticable; and a structure with a rectangular grid exposes longer and more obviously related straight lines. It becomes more noticable in the landscape. However, my choice of a hexagonal grid is primarily aesthetic rather than rational.

Realisation

However, I've now doubtful about cast concrete. I don't think I can guarantee the engineering qualities of concrete I can make on site. I could as I originally intended cast concrete units in the void and hire Alex's Unimog to move them to site, so that is still a real possibility, but these are heavy units.

Against it, concrete has very high embodied energy, and I really would have to hire an engineer to check my structures.

For it, concrete is extremely durable - there aren't any doubts that it would stay up for my lifetime.

I've considered a wood epoxy composite structure. The problem with that is that if the epoxy encapsulation is breached it will rot, and lose structural integrity; and it's hard to imagine that it can support the overburden required for good soil insulation, so insulation would need to built into the structure. Which could be done. For the roof sections, the 'well it might rot' problem is to some extent mitigated by the fact it can't be buried deep - if a module rots, it can be unburied and repaired or replaced.

However, one of the important considerations is that this is a dwelling to grow old in. As I get older, my ability to do repairs myself reduces, and my ability to pay others to do repairs also reduces. If the structure has ongoing maintenance problems it will become unsustainable.

If I'm dealing with a structure which cannot sustain a heavy overburden, paradoxically larger modules become easier to achieve. Instead of four 4.8 metre domes, I could have fewer, bigger ones. But actually the small domes have two significant advantages. Firstly, I can build them one at a time, as I can afford them. A single 4.8 metre dome would be a small but tolerable living space for next winter. Two 4.8 metre domes - the service and the kitchen dome - would make a perfectly acceptable space. And realistically that is almost certainly as much as I can afford for just now.

Equally, if I'm not designing in a heavy material with a significant overburden, the dome is no longer form following function: it serves no functional purpose at all. It becomes, in fact, a sculptural conceit - and one which does not come for free. It makes the whole structure taller - and thus harder to bury - than flat ceilings. Like the hexagonal grid it becomes simply an aesthetic conceit. Yet it remains one that appeals to me. I believe it will make a graceful space. Furthermore, actually, a wooden dome lined with birch plywood becomes an even more graceful space than a concrete one.

So the compromise solution - concrete walls and wood/epoxy roof - seems the most attractive at present. I think. I'm almost decided.

Friday, 18 February 2011

The Fool on the Hill

I've sold my house and am buying, in effect, a field. And a bit of wood and a share in a common, but basically a field. This is foolish. There is no planning permission on the field, and I'm unlikely to get any. Also, it's still possible that the deal to buy the field will fall through, but my house is sold. This is even more foolish. The field is five hundred feet above sea level, at the top of a very windy ridge. This is getting idiotic. Because I thought I would have more money than I've ended up with, I'm buying more land than I strictly need; and the consequence of that is that even if I get planning permission, I don't have much money left to build with. This is mad. Oh, and speaking of madness, I'm recovering from a bout of mental illness. At least, I think I'm recovering. So, this really is insane... Oh, and I don't have any income. At all. I could claim benefit - my doctor would certify I'm not fit to work (and he's more or less right) - but I've chosen not to. This is crazy.

But. But not that insane, I'd like to argue. Not wholly irrational. There are reasons. I'm not certain that they're good reasons, but...

I will have enough land to be self sufficient, which if I'd been more prudent I wouldn't have. The land, despite its altitude, is actually good; it's well drained, faces south west, and grew a barley crop last year. It's even soil-association certified as organic. I could live on what it can produce. I probably have enough wood to be sustainably self-sufficient in firewood.

Also, my breakdown over the last two years - which got quite bad - was at least partly because of the stresses of a failed relationship, and of working eighty-five miles from home. I couldn't sustain either of those things. I certainly couldn't sustain both together. I've no income because I lost my job, and I lost it because I could no longer do it. I'd planned to keep working until I could afford to buy my ex-partner out of my house, but I clearly can't do that. So I've sold my house in order to separate from my ex-partner. I couldn't have bought any house in my home valley on the money I thought I would realise from doing that, let alone for the money I actually did realise.

So the field is not necessarily a bad thing. Obviously, if I can't get planning permission I can't legally build a house on it. But there are workarounds. A couple of weeks ago - on two of the wildest nights of the winter - I slept in a yurt. It was a good, comfortable, pleasant, warm space. I could live in one (although I'd have to give away a lot of stuff). As it's a tent, it doesn't need planning permission. Of course, you're not supposed to live in a tent, but, on my own land and hidden by my own wood, who is actually going to stop me? And, importantly, I can actually afford a yurt - even a good one.

Of course that isn't the plan. The plan is to get planning permission to build something comfortable and interesting. But it is a fallback if that should prove impossible. And, in the meantime, I have to be living in my field in ten weeks from now - because I've borrowed a bothy for ten weeks, which keeps me warm through the rag-end of winter. But in ten weeks time it has other tennants, and I must be gone.

So this essay introduces a series of other essays which I'll post from time to time as the project develops, using as title my new persona:

The Fool on the Hill.

Wednesday, 2 February 2011

On Yurts

The last two nights I have mostly been sleeping in a yurt. No, scratch that. The last two nights I have entirely been sleeping in a yurt - it is much too cold to leave a foot stuck out for the sake of a meme.

Outside, that is. Inside the yurt it is quite startlingly warm - certainly much warmer than I would be at home. A small centrally located woodstove heats the space exceedingly effectively. My second night in the yurt was, coincidentally but rather fortunately, the windiest night for a year - and one of the wettest. In the depths of this cold, wet, violently windy night in early February, the yurt was cool. But not colder than I should have been at home, not draughty, and (apart from a slight anxiety about a tree actually falling on it) not insecure.

This yurt is from Yurts Direct, and is, I believe. authentically imported from Mongolia. It's about 6 metres in diameter - frankly spacious and generously propeortioned; it is in itself a work of art. The curtain which lines the wall has a damask weave with a crysanthemum pattern, in fabric somewhere between ivory and gold. The poles of the roof - some eighty-one of them - together with the roof crown and the two posts which support it, are of a burnt orange colour apparently individually hand painted, and yet with a regular repeating pattern, as are the doors. The doors comprise two inner doors and a single outer door, all housed in a substantial and rigid wooden frame, with windows in the inner doors and on either side of the door opening.

A curious thing is that while there is a cord to tie the outer door open, there appears to be no mechanism for latching them shut, short of leaning something heavy against them. And this matters, since it's been extremely windy both nights. Which raises another issue - there's remarkably little sound insulation. While only occasional gusts rattle the crown cover, the noise of the wind in nearby trees is loud.

At the eaves the roof is certainly less than 1500mm from the floor; at the crown ring, about 2300, and at the top of the crown perhaps 2500. What this means in practice is that I can't stand upright within one metre of the wall, but in practice this doesn't matter since the space against the wall is naturally used for seating and storage, leaving the main area of the floor free.

Although the only fenstration is the (small) glass panels in the door and the transparent sections of the crown cover, they let in a surprising amount of light in daylight - and from my bed at night I could see stars.

The floor of this yurt is made of (apparently) chipboard flooring panels, which are supported off the ground on sturdy wooden joists laid on pillars of concrete breeze blocks. The floor is not part of the package you get from Yurts Direct, but is something you have to construct for yourself.

This yurt cost £4,000, and similar yurts are available now for £4,495 (Yurts Direct describe it as a 'size 5'). Quality yurts made in Britain by (e.g.) Woodland Yurts cost about the same or slightly more. That isn't an unreasonable price - there's quite a lot of work, and a fair bit of material, in one of these.

As low cost housing for rural Scotland, how does it stack? This yurt is, I think, generous and elegant living space for one, and adequate but a bit tight for two. Indeed, a single person would get away with a smaller one. It doesn't, of course, have anything like a bathroom, which would horrify the planners. It is adequately warm with the burner lit, and clearly adequately wateerproof - this yurt, which has been up all winter, shows no signs of water staining anywhere, despite the relatively low pitch of the roof.

Most of the materials could be sourced locally in rural Scotland. The frame is wooden. The insulation is wool felt - and let's face it, we're not short of wool. The outer covering is canvas, which could be flax (in this case it isn't, but it could be). In terms of durability, the frame, with reasonable maintenance, is likely to be good indefinitely - certainly for a lifetime. Also, individual components of the frame can be individually replaced with little impact on the surrounding structure.

The canvas covering is likely to have to be periodically replaced, perhaps every ten years. The layers of felt will also need periodic replacement. Apparently it is a good thing to dismantle and overhaul a yurt at least annually, and I can clearly see the sense in this.

The major problem with a yurt in Scotland is of course damp. If the stove is not regularly lit, moulds and mildew attack the canvas and felt. This shouldn't be a problem in a yurt that's permanently inhabited, provided there is a reasonable supply of firewood. There's obviously a risk of fire; a yurt which I have seen which caught fire burned to little more than a ring of ashes. In a yurt made predominently of natural materials there should not be a great problem with toxic fumes, and, being all one space, there isn't a complicated route to find to the exit. So whether the risk to life of fire in a yurt is greater or less than the risk in a conventional structure I couldn't say. However, it's certain that in the event of a fire very little of what is in the yurt could be saved.

I don't know what happens to wool felt in the long term. People I've spoken to talk about infestations of mites or insects - probably something like the chitin-eating silverfish - and this sounds somewhat unpleasant. But inorganic felts - fibreglass, for example - also present problems, not least long term environmental problems in disposal.

The stove in the yurt I stayed in is a locally made one, not of very high quality, but it stayed in both nights even with my inept management. Good stoves suitable to use in a yurt are, obviously, available.

In summary, I was sleeping in the yurt to test-drive it - to get a feel for whether it would be a temporary dwelling I could survive in until I get planning permission for my permanent dwelling. And the answer, simply, is that it is. But - and it's a big but - it's not cheap. The combined cost of the yurt and the platform it sits on and a suitable stove add up to a fair proportion of my available building budget. On the other hand if you turn the equation on its head and say the yurt is the permanent structure - and it is comfortable enough that one could do that - then suddenly it does not look expensive at all, but on the contrary very cheap.

Sunday, 23 January 2011

The Hide

The modular sousterran idea is all very well but I have to survive somewhere until I have planning permission to build it. I can't afford to rent, so I'm pretty much going to have to live – while I'm at home, at any rate – on my land. This design exercise is to see what is the cheapest and least conspicuous living space I think I can cope with through two winters. Cheap obviously means small, but surviving through winter means reasonably well insulated.

This design is fundamentally based on my present bed, which is an IKEA loft bed with a desk and bookshelves underneath – a quite cosy and comfortable working space. I started from there and thought, 'OK, how much more do I actually need'. A design constraint is the spacing of trees in my wood. They've mostly been planted at pretty exact two metre intervals, although the rows don't precisely align. I can, of course, cut trees down – it's my wood, and, furthermore, it needs to be thinned – but in the interests of hiding the hide I don't want to cut too many down. It won't be good for the planners to know I'm living on site while I'm applying for permission to do so.

The plan is a hexagon of side 1200mm – basically, that's the biggest hexagon I can fit onto two sheets of plywood. I could get a bit more space by using a 2400mm cuboid, but cuboids are ugly and that's 25% more wall. Also, it's easier to fit the hexagon into the wood than the cuboid, which would definitely need trees cut down.

It's beneficial to have the cabin off the ground to avoid damp. Having it head-height off the ground means you can use the area under it as sheltered storage. There should be no need to kill the trees that support it, two poles lashed crosswise to four living trees should be fine.

The downside of the hexagonal plan is the bed ends up an odd shape – it is 2400mm long on its long side, but only 1040mm wide and only 1200mm long on its short side. It's big enough, I think, provided any concubine is friendly!

The hide as designed has a wood stove for heating and basic cooking, but there is no lavatory, bathroom or laundry – those facilities will be available in the Void. A stove is quite expensive, of course, but I think it's essential.

Construction

My idea is to construct the hide as two modules and six roof panels off site, under cover, transport those modules to site without their insulation and final outer cladding, erect them, insulate and clad them. The module structure will be primarily WBP plywood with softwood framing, assembled using the wood epoxy saturation technique, so pretty durable. Insulation will probably be 100mm fibreglass felt, although if I can find something more ecological that I can afford I will. All panels, including the floor, will be insulated.The rear module will contain the built-in desk, bookshelves, cupboards and bed. The front module will be considerably simpler, containing the bunk ladder and wall cupboards. The modules will bolt together – the reason for applying cladding on site is that the cladding will cover the bolts. Also, of course, the unclad modules will be lighter and easier to manhandle.

The cladding will be tongue and groove softwood weatherboard painted with an olive drab exterior preservative paint, but nevertheless is not expected to have the same life expectancy as the core structure – it can be replaced if needed. In order to prevent nailing the cladding on from breaching the encapsulation of the epoxy-protected core structure, sacrificial 25x50mm strips will be bonded on for the cladding to be nailed to.

It would be much simpler and cheaper to make a lower, hexagonal roof. Making the roof conical is an architectural conceit. The roof will almost certainly have to be cut on site to make room for the trunks of the supporting trees. It is built as six panels each having a flat sheet of plywood as its inner surface, a flat plywood soffit board, and an outer surface planked with tapered softwood planks. Between the inner and outer surface will be insulation as on all other panels. Some arrangement for ventilation will be made at the eaves. One of the panels will have an aperture designed for the stove pipe to pass through. After the hide has been erected the roof will be covered with tarred felt, and the final top cone, probably of stainless steel sheet, will be fitted.

Living

The hide described in this paper really is small, and in cold wet weather is bound to be claustrophobic. Nevertheless with a small wood stove in a small and well insulated space it should be cosy, even in very bad weather, provided the door fits well! In better weather, and to entertain anyone, it needs to be extended, and this can most simply be done by providing an awning. An awning to provide a 5 metre square sheltered outdoor space would mean felling four trees.It's probably not possible to provide a cludgie in the wood as the drainage ditches all connect back to the Standingstone burn and are sufficiently closely spaced I doubt you could get the requisite distance from running water. I'll check this, because some sort of loo would be a good thing.

A stove of the sort used in yurts would provide adequate basic cooking; in practice except for baking bread I don't often use an oven. For more elaborate cooking we will probably eventually have a cooker in the Void.

I'm not sure about electricity – some form of light is going to be necessary in winter, otherwise it's going to be a little grim; and it would be nice to be able to use my little laptop without having to go up to the Void every day to recharge it. But solar panels are not going to work in the wood, and mains is not on for all sorts of reasons. Even a small wind generator would attract attention.

There's obviously nowhere near enough storage space in this for all the clothes I use regularly, or all my tools, computers, books and things. This is minimalistic, temporary living, and most of my gear will have to be stored in the Void.

Thursday, 20 January 2011

Sousterrain revisited: there is a plan B

Having considered my earlier note on the design of a sousterrain for a month, I'm now going to rip it up and start again.

Reasons for not building in concrete

Reasons for building in timber

Lightweight structure

Overburden

Temporary structures

Hybrid structure

Plan B

- Start immediately (in March) to build one experimental dome in epoxy encapsulated timber with an intention to have it habitable by May

- Erect that in a suitable place 'off site' (and not earth sheltered) until planning permission has been obtained.

- When planning permission has been obtained, dig out the platform (the entire platform large enough for all four planned domes).

- Lay suitable foundations for one dome.

- Disassemble the prototype dome and re-erect it on-site.

- Back-fill over that dome only, leaving the remainder of the platform clear.

- Occupy that one dome, at least for winter 2011-2012; build other domes in a similar fashion at funds allow.

Tuesday, 18 January 2011

The joys of data transfer

OK, so, at this stage the main thing this blog is for is to find out how to import existing blog posts into Blogger. Brief summary: my existing blog uses a blogging engine I wrote myself back in 2000; it's quite a good blogging engine but it's not used by very many people because I didn't promote it enough back in the day, and so it's time to end-of-life it and migrate the existing users to something else.

Blogger has a mechanism for exporting and importing blogs. So, I thought, it ought to be possible to generate the export format, which is documented here, from my existing data and then import that. From the documentation it was clear that the format was slightly bizarre - a well formed XML wrapper around data which is actually XML and presumably also well formed but is represented as text. However, I generated stuff that looked right to me according to the documentation, and it failed to import.

Worse, the error message given was terse to the point of unusability, and there's apparently no documentation of the error codes available on the web.

So the next thing to do was to export this blog from Blogger, and see whether the export file format looked anything like the documentation. And, guess what, it sort of doesn't. Which is to say that while the file format shown in the documentation is a very small subset of what's actually generated, it is such a noddy example that it doesn't even nearly represent what one needs to generate.

And, of course, there's no guarantee that even if I did succeeded in generating all the cruft that's in the format as generated by Blogger, I'd get my data to reimport - since the format includes magic identifiers which may represent objects in Google's persistent data space.

So it may be time to think of other ways to work around this.

Monday, 17 January 2011

End of eating dogfood

I can't help being slightly sad.

Monday, 29 November 2010

Site specific low cost housing for a windy site

Part of the issue of building housing on the site we're considering is the wind speed, which is high. I imagine we're all going to want homes which don't take a lot of energy to heat, and the wind-chill effect on exposed walls is going to be considerable. The parts of the site which are most exposed to the wind are also the sunniest – the southern and western slopes. Of course, one can insulate, and straw bales are worth considering.

Sustainable?

Visual impact

Elements

Dome segment

Pillar

Flying Buttress

Eve

Building method

Dig back into the hillside

Lay drains

Level platform

Pour slab

Erect pillars

Erect uphill walls

Erect terrace retaining wall

Part-backfill the uphill side

Erect flying buttresses, eves and (possibly) lintel arches

- Embed a tensile steel reinforcing belt as low as possible in each dome;

- Construct separate armatures for each dome and leave them in place until all domes are cast and cured.

Erect domes

Fit chimney outer

Fill valleys between the domes

Lay upper membrane

Backfill

Install glazing

Fit out interior

Rough costings

| Sousterran: quantities and mass | ||||||||||||

| Concrete option | Cladding | |||||||||||

| Constants | Unit | Item | Unit | Price | per sq m | |||||||

| Mass of 1 cubic metre of concrete | 2400 | Kg | Bituthene 3000 | 20 metre roll | £163 | £9.03 | ||||||

| Mass of 1 cubic metre of soil | 1700 | Kg | Styrodur 3035CS, 30mm | 14 sheets at 1250x600mm | £70 | £6.67 | ||||||

| Price of 1 cubic metre of concrete | 100 | Pounds sterling | Styrodur 3035CS, 60mm | 7 sheets at 1250x600mm | £70 | £13.33 | ||||||

| Price of 1 8x4 sheet 15mm exterior ply | 40 | Pounds sterling | Total, with 30mm | £15.69 | ||||||||

| Price of 1 sq metre concrete blockwork | 10 | Pounds sterling | Total, with 60mm | £22.36 | ||||||||

| Dome radius (long axis) | 2.4 | metres | ||||||||||

| Area of dome floor | 14.98 | square metres | ||||||||||

| Area of dome surface | 36.19 | square metres | ||||||||||

| Number of wall panels | 11 | at | 4.8 | sq metres | ||||||||

| Elements | Area sq m | Thickness m | Volume cu m | Mass tons | Concrete Cost | Cladding cost | Number of | Total cost | Total mass | Shuttering sheets | Shuttering cost | |

| Floor | 104.83 | 0.1 | 10.48 | 25.16 | £1,048 | £399 | 1 | £1,448 | 25.16 | 1 | £40 | |

| Dome | 36.19 | 0.1 | 3.62 | 8.69 | £362 | £809 | 4 | £4,685 | 34.74 | 42 | £1,680 | |

| Dome segment | 6.03 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.45 | £60 | 24 | 34.74 | 7 | ||||

| Pillar | 0.5 | 1.2 | £50 | 17 | £850 | 20.4 | 6 | £240 | ||||

| Eve | 1 | 2.4 | £100 | 5 | £500 | 12 | 4 | £160 | ||||

| Flying buttress | 2 | 4.8 | £200 | 4 | £800 | 19.2 | 6 | £240 | ||||

| Wall | 4.8 | 0.1 | 0.48 | 1.15 | £48 | £75 | 11 | £1,357 | 12.67 | 0 | ||

| Overburden | 104.83 | 0.2 | 20.97 | 35.64 | £0 | 1 | £0 | 35.64 | 0 | £0 | ||

| Subtotals | 50 | £9,639 | 194.56 | £2,360 | ||||||||

| Total, cost | £11,999 |

The fool on the hill by Simon Brooke is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License